What are the markets telling us? Peak S&P 500? Inflation break-out? Bond break-down?

Markets yearn to be free. Is this the year they will finally be freed from central bank intervention and manipulation?

The following article was originally published in “What I Learned This Week” on February 8, 2018. To learn more about 13D’s investment research, please visit our website.

In WILTW January 11, 2018, we warned the U.S. equity market was heading for a top. Have we seen the top? Or, was this a much-needed correction of an advance that had reached extremes with the ultimate top still ahead of us? The answer is unknown, but the decline since last Friday occurred exactly when it was supposed to.

Even perma-bears expected the parabolic advance to continue despite the fact the Dow was close to 30% above its 4-year moving average, a very rare event. Central bank liquidity is shifting from expansion to contraction. The Fed’s balance sheet run-off is scheduled to increase this year from $20 billion a month to $50 billion. While the Fed has been withdrawing liquidity for some time this was offset by extremely expansionary policies by the ECB and BOJ — and that is about to reverse.

The BOE surprised the markets today by announcing that it may raise interest rates sooner and by more than previously forecast. Also, as a precursor of what could happen globally, tax filings in the UK suggest wages are growing much faster than reported. In Germany, the new labor agreement granting a 4.3% wage rise over 27 months shows that unions have a very strong hand in labor negotiations due to the economic boom.

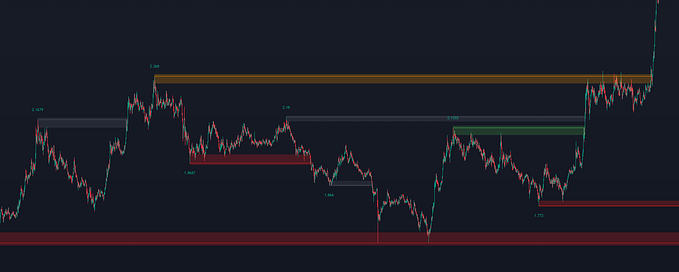

As we discuss in section 3, the blow-out in the U.S. federal budget deficit will require annual borrowing of $1 trillion-plus indefinitely. And that is before the roll-out of the administration’s infrastructure package and other domestic spending increases that are brewing in Congress. It is no surprise, then, that the U.S. Treasury long bond and the dollar index have broken down from what appears to be a major head-and-shoulders top. One can only ask if this is the year of a perfect storm for long bonds and who will be held accountable?

This week, we saw for the first time the machines operating on the downside. We have warned for some time that the major risk in the markets would occur when algorithmic trading switched from a buy mode to a sell mode. We said in many private client meetings: “We have seen the algorithmic trading on the upside, but we haven’t seen it on the downside — except in China in 2015 and they nearly shut down the stock market to great criticism in the Western world.” Is it also possible that the new financial products — such as leveraged ETFs, risk-parity funds, volatility-targeting programs, statistical arbitrage, exchange-traded loan funds — created in the last ten years will prove to be as dangerous to the financial system as those that were created before the GFC?

One noteworthy event this week was that the U.S. dollar barely rallied despite the prospect that the Fed would need to be much more aggressive in 2018. (For what it’s worth, the U.S. trade deficit in 2017 grew 12% to $566 billion, it’s widest since 2008.) Peter Schiff of Euro Pacific Capital offered an interesting explanation this week, which dovetails with the data points above:

“But the dollar itself may be a window into the troubled souls of otherwise carefree investors. Even in the market surge of the past decade, there have been some isolated moments when daily declines are significant. By looking at what “safe haven” choices investors make on the market’s worst days, we can potentially see what may happen if the market experiences sustained selling.

If we look at the average of 10 worst market days each year during the five years from 2008 to 2012, 50 days when the Dow dropped by at least 100 points, we can see that the dollar tended to rally in the panic. During those days, the dollar index rallied 80% of the time, and on average rose .6% on the day. This seems to reflect that the dollar maintained its “safe haven” status. But, in more recent years, that has changed considerably. Averaging the 10 worst market days of each year in the market from 2013 to 2017, the dollar fell on those 50 days by approximately .3%, and it only rose 26% of the time.

This shift in sentiment could be extremely significant in the years ahead. This is why a simultaneous collapse in bond prices and the dollar could be so significant. It could show that rising interest rates do not reflect improved growth as so many stock market bulls conveniently claim, but a loss of confidence in the dollar and the creditworthiness of the United States.”

Our argument has been for some time that the U.S. stock market and the U.S. dollar are the most crowded trades on the planet and that capital concentration always leads to capital dispersion. And that dispersion will flow to the rest of the world — especially the longest neglected markets, which we have been pointing out to you for many months.

Markets yearn to be free. Is this the year they will finally be freed from central bank intervention and manipulation?

This article was originally published in “What I Learned This Week” on February 8, 2018. To subscribe to our weekly newsletter, visit 13D.com or find us on Twitter @WhatILearnedTW.